What happened the metaverse? Lessons from the dot com bubble

It is nearly a year to the day that Facebook CEO and pantomime villain Mark Zuckerberg announced that his company would be rebranding as Meta.

It was a huge statement about the direction of the metaverse, which many were beginning to declare would encompass everything from socialising to transacting, working to entertainment.

And as I wrote about last week, it is a bet that has turned sour for the billionaire.

But across the market, are we seeing the same pattern? Is interest in the metaverse dwindling?

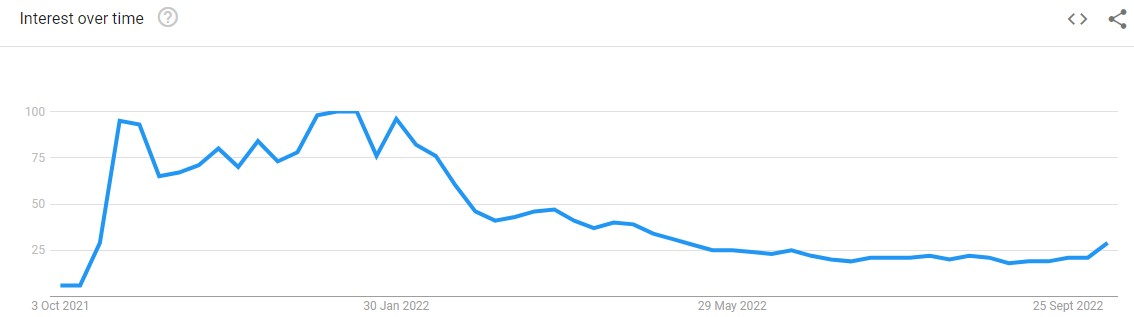

The first port of call I went to was Google, where search analytics paint a picture of a big spike in interest for the term “metaverse” after Zuck went all-in last October. Not long after, a steady downtrend.

A damning chart, no doubt. But how much of this can be attributed to the concept of the metaverse itself, and how much is merely a consequence of the wider macro bear environment?

It’s hard to say, but there is no questioning that a lot of metaverse projects were significantly overhyped. It is possible to believe in the metaverse, yet simultaneously have the opinion that a lot of the tokens in the space are either overvalued, offer minimal utility, or both.

One thing I still cannot figure out is why so many investors are willing to pour cash into anything remotely metaverse-related, regardless of whether the investment has a verifiable plan to gain market share in the eventual metaverse, whatever that may look like.

Sure, this blind punting has fallen off a cliff now that the market is so brutal, but a lot of these companies still have mammoth valuations, even after declines of 80%+.

The dot com bubble

Let us not forget that the Internet has changed the world immeasurably, going beyond the expectations of even the biggest bulls. And yet still, think of how many companies went under during the dot com bubble burst.

A poignant reference is Priceline.com. You may not recognise that name today, but it was once in the biggest Internet companies around. Its thesis was enticing: of the half a million airplane tickets going unsold every day, customers could use Priceline to enter the price they would be willing to pay.

In such a way, airlines offloaded their excess inventory, customers picked up cheap seats, and the market equilibrium was found. It kind of makes sense, right? And all the while, Priceline were taking a cut of each transaction.

A seemingly sensible business plan; a gap in the market; and something that would have had people at parties responding with “oooh, that is so clever”.

It launched in 1998, and within seven months it had sold 100,000 tickets. Only 13 months after launch, it went public at $16 per share. It spiked on this first day to $88 and settled at $69. There were plans to expand further too – why couldn’t the system work similarly well in areas such as hotel rooms, train tickets, even mortgages?

Its $69 close after its IPO day gave Priceline a valuation of nearly $10 billion. It was the most valuable company in the Internet’s brief history.

And then it fell 94%.

This story is not unique, of course. The Nasdaq shed over a third of its value just over a month after peaking in April 2000.

What does the dot com bubble have to do with the metaverse?

Which brings me to my point. You could believe in the Internet without believing in all the companies that were claiming to be “Internet companies”. These companies were notorious loss-makers, with the concept of a profit unheard of in the dot com days. Priceline, for instance, ran up losses of $142.5 million in its first few quarters.

And yet, the Internet obviously changed the world.

There are many Pricelines out there today. Perhaps the dot com era’s “profit” is the metaverse era’s “utility”. Before investing in any of these tokens, ask yourself what do they actually do? Do they have a clear roadmap towards leveraging the metaverse to create something of tangible value? Most importantly, is there any utility here?

They seem like basic questions. And that’s kind of the point. They really are basic – but so many coins cannot answer them. Let us not forget how easy it is to create a cryptocurrency; a simple copy and paste technically creates you one. Combine this with the fact so much cash was flooding into the space – both from investors and through VC’s – and it’s no surprise that so many tokens have completely collapsed.

For every Amazon, there are ten Pricelines.

And the other thing that needs to be mentioned here is there is (obviously) no guarantee that the metaverse will become remotely as impactful for society as the Internet was. Even with the Internet hitting every single imaginable target, there is still a raft of Pricelines out there. Imagine how many there would be if the Internet flopped?

Final thoughts

Just because you believe in the metaverse, don’t blindly punt anything with the name “metaverse” in it.

For the foreseeable, of course, every single crypto – metaverse or other – will continue to follow the stock market, such is the macro environment right now. So even the ones which offer utility, and could be well placed to otherwise excel, will not yield returns for investors as long as the wider market continues to lag.

But even if the market recovers, metaverse tokens still have to prove they actually accomplish something – which many cannot do. As always in investing, it’s important to therefore do due diligence on the coin in question, block out the noise, and ask yourself those basic questions as discussed above.

Don’t let the metaverse seduce you with sweet nothings whispered in your ear. A utopian dream won’t pay the bills at the end of the day, and we have the dot com bubble as evidence for that.